Note 01: The Ethics of the Middle Finger

An Academic Essay for a Professional Ethics class; On Acculturation Strategies and Metha-ethical stances

Consider switching from your email inbox to the website or app for a better experience.

Dearest Stranger,

The following essay was my pride and joy in third semester. Since this newsletter is often talking about ethical literary citizenship and consuming better, today i’m sharing this nugget with you out of a relevance of what my personal ethics are.

In the future, I wish to use more academic essays to annotate them on here as a means to connect the missing link that I’ve felt this newsletter has needed.

I hope you enjoy.

Introduction:

Morality melts into life’s fabric through a web of chronicles that sink deep into the roots of existence. Meta-ethics and its ceaseless desire to understand such a varying nature, shakes hands with life as an obligatory practice strengthened through our social affinity; for this essay's case, as acculturation strategies the way postulated by Barry’s model.

I will be aiming to discuss three phases of my journey to reflect over the two;

Firstly, to understand my perspective on the nature of ethics, I will explore how before I could unpack this question, I had to sit with the discomfort of realizing how this understanding sat wrong in our chests, wearing the face of cultural servility.

Secondly, to discuss participation in life after this realization, I will explore how I settled on Integration and Meta-ethical Relativism with a consequentialist approach because socializing is a crucial element through the point blank reality of being born in a society (There would be no need for acculturation, even in the marginalization phase/state if I was a hermit).

Thirdly, my present approach to life and a proper reflection of the future — including whether my current stances are elastic enough to withstand time, and if not, what a potential new strategy would look like.

Part 1

What I want is to be free, which means I move with a value on life unparalleled to any gain I might have from the negotiation required in mass killings. But then too, my morals come from my own needs in my life. Of course I have liberatory goals— my life is better when everyone is free.

— When I say I do Not Care for Morality: A Statement of Purpose by Ismatu Gwedonlyn

Often overlooked, the 7 to 10 year old can be a beacon of simplistic moral standings that can be the foundational answers to the bigger problems. For the sake of exploring meta-ethics, I want to begin by relaying how I had once been asked;

”Why do you think the middle finger is bad?”

On a balcony, we had just begun acknowledging out loud about differences within peers back then, and “cool” was what all 7 year olds strived for. It looked different for everyone, but a disillusionment from authority was a major facet of where in ‘cool’ I perceived myself to belong. So the inevitable reply came with gutsy creativity,

“I don’t think it is, we just made it up.”

There was no god that had equated our middle finger with the male genitalia, and if human beings had equated it to that, then kid Bakhtawar could surely equate it to a magic wand and wave it around the rest of the afternoon playing witches and wizards with her friends with no repercussions, couldn’t she? Was this good, or bad? I remember vividly thinking that reclaiming (read: turning, for kid logic) a seemingly rude gesture into one of magic goodness could not be bad. It must have been quintessentially good in the way normal good wasn’t. Not when most kids cursed without even knowing the meaning of the words they were uttering, or did good just within the constraints that were laid out as it is for them.

This is relevant because as the afternoon waned, an adult caught sight of our transgressions; an out of context scenario of our heroine heatedly shouting at the wicked witch to stop trying to steal hair from the pretty princess while waving the middle finger in her face threateningly. The humor of the situation aside, when the adult was a white woman who proceeded to complain to our then immigrant parents about our indecency, us 7 year olds could not fathom why our magic wands were being treated as defiance and lies to our parents who knew what we were really doing.

For the academic undertone of this essay, there are a few things I cannot allow you to infer:

Firstly, finding lucrative ways of being good was a personal mission for kid Bakhtawar. Just good was uncertain, as seen above — there was no real middle finger being raised with indecent expressions, and there was a lack of understanding from authority of this reclaimed exceptional good. This led to a reputation that followed me. One that often meant the nervous smiles that slipped into my face when a perpetrator was at large marked me as the transgressor most times. Furthermore, as if these misunderstandings were not enough, there was no proper communication of why my actions were perceived as bad after an incident. They just were. The adults knew me and they knew good irrevocably, which was an insufficient answer that did nothing but widen the gap between myself and a trust of what the elders had to say.

Secondly, this is a mild example demonstrating a frequent mismatch between myself and the way in which I grappled with being good. Being good was a fluctuating device used by my elders with no real reasoning given to me. I was to act exceptionally well behaved and active in front of some guests, and with others that same behavior would not apply. In some instances I could indulge myself while in others it seemed that that very indulgence was sacrilegious. Without reasoning, there was no strength behind these random circumstances and their random form of conduct. Not communicating to me why my misconduct was negative felt wrong. The morals behind everything was up in the air — yet, almost absolutist in the way that my way of practicing life was bad.

Thirdly, this snippet is given to you to showcase that:

I spent early formative years with a marginalized acculturation strategy. I found myself believing my moral actions to be bad due to the reactions they received, and the ones being told to me also sat unreasonably in my stomach. I aligned neither with the root morals of my family, nor the morals I was hypothesizing to replace those root morals. Especially, when social adaptation was important to me.

Despite my unease with this constant flux of what “good” was I had come to some conclusions towards the end of my marginalization period, which lasted well into my formative teen years. One, that good was often misconstrued with actions that increased social likeability, often with a short term lens, instead of causal good. Two, the goal for why one happened was not an undesirable one, meaning that social likeability did not have to cause harm. Three, that “good” because of two was relative and compromise could be a good circumstantial answer in the divide between adults and myself, a consequentialist outlook being crucial to dictate the extent of compromise between both parties emphasized by the matter of our free will. All of this, given life’s dynamic nature and our progression as a global civilisation, matters immensely.

As a kid my idea of morals (which I believed to be the “good” I was told to adopt) was intuitively connected to the idea of minimizing, eradicating, or reclaiming harm to turn it into healing, reparation, protection, care, motivation etc. I also came to understand that this looked different for everyone because of the gap in the way I thought and the elders thought.

Part 2

No evasion at all will keep us safe; my moral compass (alarm and dis-ease at our current systems) then guides me towards what is practical (work in all manners to topple the system). There is no freedom in lying to ourselves about our conditions. Freedom comes from successful overthrow transitioned into popular sovereignty.

— When I say I do Not Care for Morality: A Statement of Purpose by Ismatu Gwedonlyn

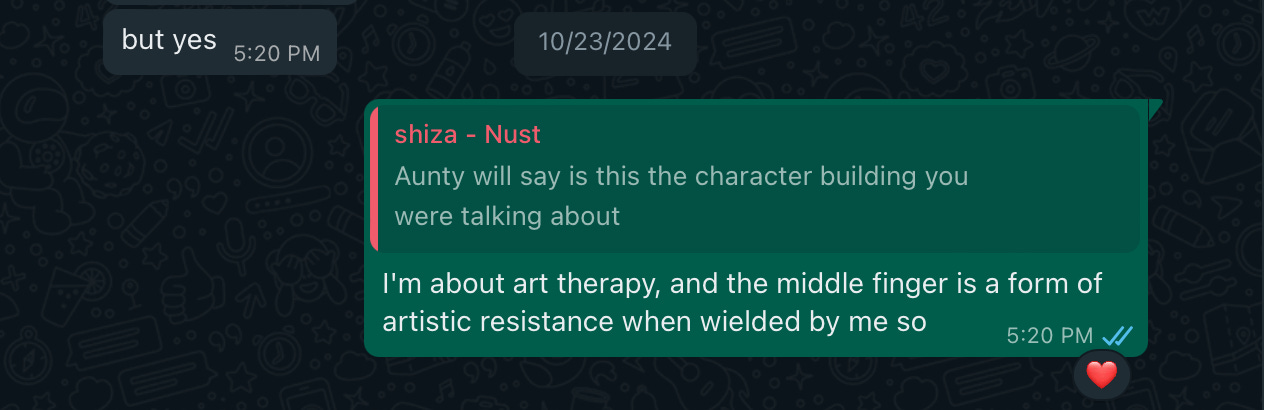

I was a stubborn kid, and I’m a stubborn person. That is to say, the image on this page is my instagram feed. Point to note; the middle finger persists today as a nuanced and more complex symbol that has settled on certain ethics, and then reconstructed them — depending on the situation.

I had developed a meta-ethical understanding long before knowing what to do about it (i.e which acculturation strategy to adopt); Relativism through a consequentialist lens. I answered this ignorance through puberty, ages 13-16. It was the only way I could humanize both myself and authority figures, and it was the juncture that led towards my acculturation strategy. We were both people.

The dawning of this phase came with the understanding of what it meant to be nestled deep in the stomach of a patriarchal machine. After spending a life in Iquique, Chile — I was moving to my parents homeland. To understand the depth of this, read the following excerpt from a reflection of my cultural identity for an Anthropology course last semester:

“…It is then not a matter of me being a third culture child, but a matter of being born in the heart of a family in which immigration replaces the blood in our veins. ‘Homeland’ then, is a concept too far-fetched to embrace. For me, my parents, my grandparents, we were all either immigrants or third culture children.

My parents' generation, also with this displaced sense of self, found themselves moving abroad in herds. My uncles, then aunts, then my own father. I have Portuguese aunts, and Japanese aunts. French and British raised cousins from them. The brown skin on me is Asian sheep, in Latin wolf clothing.”

Before the move, I had lived a sheltered life that was confined to my family and Pakistani family friends. School already estranged me from a lot of the rules my south Asian parents imposed, but still in a country and landscape I was familiar with, it mattered little. I had similar immigrant friends from Pakistani parents, and so we had created our own little culture within that context. My only discomfort within this social context was our class difference for a brief amount of time. After moving, this specifically niche outlook failed in front of Pakistani bred and born individuals along with my class context.

Both of these are important to note because I knew to an extent what it was like to be homeless; jumping from one borrowed room to another in the houses of different generous community members. When my family finally constructed comfortable stability (two bedroom apartment, food, and toys!) for the briefest of moments, moving into a big house (three bedrooms, two sitting rooms, three bathrooms and more?!) in another country felt as though money mattered more than stability. There were more factors to this conclusion in the form of moments within a financially unstable family, but this was the moment my family’s mentality made sense. It didn't sink in, but it made sense.

Both the culture and my class had changed in a drastic way after the move. The problems from Part One only amplified themselves, so to hold on to any semblance of individuality and social acceptability it had become more important than ever to sort out where I had to conform and where I could influence my loved ones. A disillusionment of the invincible authority was important for my conclusions, and I had faced that quite early on. Integration became my only option for stable living and loving — both different and equally dear to me.

I could have chosen to just live with the consequences of isolation due to my differences (separation), or the consequences of conforming completely by losing myself into the toxic as well as wholesome patterns being regurgitated to me by my grandparents now (previously parents) (assimilation), or even the consequences of continuing to feel isolated from my own personhood and autonomy as well as my family and loved ones (marginalization, and my then state) — but the consequences of changing the perspectives of toxic patterns in my family, while getting to enjoy the better parts of these patterns with them was a good choice to me. All of these would’ve been hard, but I also knew I had the same human flaw and could also mess up and cause harm. If I had chosen to make those harmful mistakes without community, that would’ve been a worse consequence than having to make those mistakes with community, and still live to have the credibility to hold others accountable when they made their mistakes.

Did I achieve this?

There are instances where I had to accept I wouldn’t, like when the hijab was imposed on me when I was not ready for it — I wore it still, and that became an instance that made me feel as though I had marginalized myself again (not the case), but not having done so would not have allowed my mother to see the consequences of that imposition so that she could learn not to do the same to my sisters. It also allowed me to have the conversation that would hold her accountable for the negative consequences it had for me, which became a bonding moment for us instead of one where we would’ve been further apart with no understanding of each other. Those are the instances that make me realize integration is a long term process when it is paired with meta-ethical relativism through the consequentialist lens. I could not fault my mother for her choices of me when she did not do the same to my sisters — the circumstantial and consequential outcomes both played a role which I could not dismiss.

There are other instances where I get to hold my elders accountable when they ask problematic questions from others, like why someone isn’t having kids, or bringing this fact up with others when that individual isn’t present to hypothesize an answer. Most times, I see that they know what they were doing was wrong but the short term social benefit of engaging in such backbiting makes them continue. They also do it less once they know they will be held accountable, and at times even do that themselves. These instances show how integration can cause ripples of good change which is a consequence that is important to me.

Both conclusions from both such instances reinforce why integration is my acculturation strategy of choice, which is a crucial reminder every once in a while when acting morally can be hard on the self.

P.s I eventually convinced my mom why the middle finger is reclaimable (not that she likes it any better, but I’m stubborn).

Part 3

I feel no need to be compelled by morality, or the idea of humanity as we’ve constructed it under colonialism. I am compelled by my neighbors and family and countrymen and friends. My moral compass, calibrated by my loved ones, guides me towards practicality. Revolution is love-inspired (Blood in the Eye, Jackson, page 3).

— When I say I do Not Care for Morality: A Statement of Purpose by Ismatu Gwedonlyn

There is something missing in this essay; why am I quoting revolutionary quotes about defying morality, when I’m simply talking about the progression of my everyday life and reflecting how morality is relevant in it? To answer this, what is everyday life?

Everyday life is having a career, or going to school, it is buying groceries, clothing, and essentials, it is also buying luxury commodities, consuming entertainment online, and utilizing globalized inventions like the phone, computer and the internet, it is also going out to establishments for social gatherings and spending money in them. All of this is to say that the everyday is political, and that means every action is moral or immoral in a more interconnected way than the average person thinks.

2020 came with the global Covid-19 virus, the world went on lockdown and most of us spent that time chronically online. I also spent that time with a friend group with whom I would fight people in comment sections of reels as a hobby — you read that right. We are a reactionary society due to the commodification of every little material and immaterial quality we possess, and I was the most reactive.

I would not say that all of the isolated comment section fights that keyboard warrior Bakhtawar had were morally correct — I will however say these fights collectively were the initiators of acquiring solid knowledge on controversial and political topics. May 2021 brought us a lot of noise for Palestine, and then my most dearest friend died on the 25th of the same May. Both personal and global crises radicalized me in a way I never fathomed. The reason we used to fight on the internet was because we saw someone saying something hurtful/harmful — and whether it was our collective understanding of being an oppressed minority, or class struggle, or personal identity; we could not let that go.

After that May, I had to be more than a keyboard warrior, and working outside of the comment section to produce real revolutionary change was harder than comment section fights made it out to be.

From 2021 then to 2024 now, both integration and meta ethical relativism have served me well. Especially since, the average everyday life is complacent of immorality (oppression). Not through an intentional practice, but through an ignorant one where this ignorance too is a tool enforced upon it through a greater immoral act of oppression. These stances have allowed me to see the futility of being reaction oriented, they have developed more empathy in me and given me the patience needed to study the oppressive and dying state of the world to be able to further study what to do about it.

I sometimes find myself thinking that integration will not cut it for structures like capitalism, the patriarchy, and imperialism — but I also understand how without utilizing these three structures, we cannot eradicate them at this stage either. If with further knowledge, I find the solution lies in separation, then I am inclined to adopt it. My choice in degree being a service oriented one as opposed to product oriented one, bereft of a service over material things such as software engineering etc are a form of integration that keeps this future separation in mind. I am working on developing a skill that helps me contribute to communal living systems by giving managerial, mental health related, and organizational help — and in the future perhaps even literature aids. It is these ways in which I can make my everyday life look less complacent of oppression day by day. Brief separation then looks just as important as eventual integration to me — and this is one of the root messages of my newsletter on Substack called Stories and States where I talk about the ethics of creating and consuming.

I hold on to meta ethical relativism and consequentialism because the context of a world being constructed after revolution will be a relative world. I cannot fault the entire world today by generalizing humanity as something oppressive which welcomes ignorance. Society would be static if it wasn’t relative, which is an impossible goal because we are imperfect and possess constant room for improvement. This improvement can neither happen by getting stuck in past immoralities nor without acquiring the knowledge necessary to do so.

My middle finger today signals a couple of important things to the relevant people (not without their knowledge) looking to become a part of the culture and ethics I’m progressing into. It is not just a magic wand as it was back then, nor a way to scare creepy men away like it became afterwards, nor is it a way to signal to the safe people about the secrets of my identity I don’t feel safe enough to make open yet; it is in fact all of them and more — in relative manners, depending on the consequence of its use, and its space in my integrative acculturation strategy. Before I even had to take this course, I knew it was a moral and important symbol to me given my persistent use of it and even recognition through it — now I have stronger education to back it. That isn’t to say it is important, nor is it to say it is fickle — it just is, and that should not be a problem unless harm is involved.

The End.

Behind the scenes:

They’ll come around…eventually.

An Annotated Life is a free newsletter with monthly book recommendations, mindful TBRs, literary essays, Psychology Essays and other creative expressions of my love for literature and knowledge.

Consider subscribing if this sounds like your cup of tea!